By Richard I. Gibson

保皇會

The Digging Butte’s Chinatown exhibit has been on display for three years – but it turns out we didn’t have all the cool stuff out there.

Thanks to a visit from Mark Johnson, a Montana native who teaches at the Concordia International School in Shanghai, we found an important artifact. Mark is studying the Chinese Empire Reform Associations (CERA; Chinese

Baohuanghui, 保皇會, or “Protect the Emperor Society”) in Montana, and was interested in a

Montana Standard photo of archaeologist Mitzi Rossillon holding a CERA medallion found during the dig in 2007. It came from “Feature 6,” the site demolition deposit that includes materials from the 1890s to the 1940s. Because there was no good stratigraphy, Mitzi elected not to catalogue that material.

We found the medallion in the unsorted collection this month.

The

CERA began in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1899, created by exile Kang Youwei. CERAs supported the short-lived reforms instituted by the Guangxu Emperor (reigned 1875-1908) to modernize (and to some extent, Westernize) China; his plans were thwarted by the Empress Dowager Cixi, who placed Guangxu under house arrest and he served most of his reign after 1898 as an ineffective figurehead.

More than 150 CERAs were established worldwide, including at least nine in Montana. The

Butte chapter was organized in August 1901, with Quong Loy the president. They met in various locations, including the Chinese Freemason hall (20 West Galena), 103 China Alley, and 212½ S. Colorado, which stood in today’s vacant lot across from the Mai Wah, the site of the 2007 archaeological dig that uncovered the medallion.

By 1905, the organization was actively supporting a developing army in the U.S., intended to help restore the Guangxu Emperor to power. In Butte, “the young men of Chinatown,” numbering about 30, spent many summer evenings in 1905 drilling and practicing army maneuvers “upon a roof back from the street on Mercury just west of Main street” (Anaconda

Standard, January 8, 1906). But by the following year, with financial and other troubles, the military schools were disbanded by order of leader Kang Youwei. The organization effectively ended with the start of the Republic of China, in 1912, although its successor, the Chinese Democratic Constitutionalist Party (1911-1945) and other incarnations continued to have political influence for many more years.

The medallion shows an image of the Guangxu Emperor, and crossed flags of the CERA and the dragon flag of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912; the Guangxu Emperor was second-to-last emperor of China).

Mark Johnson is working on a report on the Montana CERAs to be published in the Montana Historical Society’s

Montana: The Magazine of Western History. We look forward to seeing it!

Resources:

Baohuanghui blog. Quong Loy photo from

Butte Miner, Feb. 7, 1902 (see also Anaconda

Standard, Aug. 22, 1901); flags from Wikipedia (Creative Commons licenses). Medallion photo by Richard Gibson.

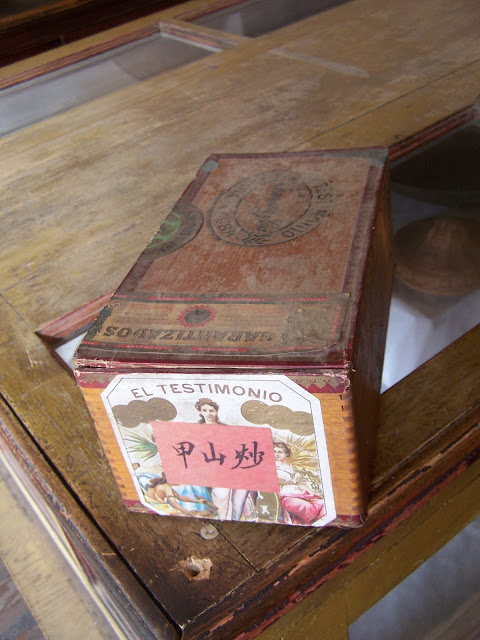

The interpretation of the label on this box is “Immortal Flower.” Immortal is certainly the second character; the first leaves something to the imagination. And “Immortal Flower” has different connotations in various traditional Asian cultures, and may refer to more than one plant.

The interpretation of the label on this box is “Immortal Flower.” Immortal is certainly the second character; the first leaves something to the imagination. And “Immortal Flower” has different connotations in various traditional Asian cultures, and may refer to more than one plant.